Conditioning Concepts

I had the pleasure of tuning in for a Joel Jameson Masterclass yesterday afternoon. During this time away from the gym it’s amazing to see how health and fitness professionals are reaching out to support both the profession and our surrounding world.

His talk was centered around how he designs a conditioning template. I’ve used a lot of his ideology over the years in my own conditioning programming and wanted to share some concepts that have worked well for me.

Step One - The Assessment

Assessing an athlete’s level of conditioning is as complicated as we want to make it. The following are some assessments that I’ve used that can be used in most gym settings with minimal equipment.

General

Resting Heart Rate

Heart Rate Recovery

12 Minute Run (Cooper Test)

Mile Run

2000m Row

Training-Specific

Deadlift Repetition Maximum

Timed Plank

Bench Press Repetition Maximum

These are all basic assessments that can be easily administered. Some further assessments to try in the event of access to equipment would be VO2 Max or Heart Rate Variability (HRV). Some current wearables offer an HRV metric like the WHOOP band and some more recent Apple watches.

Step Two - The Training Program

This is where the rubber meets the road. Too often conditioning programs consist of volume and intensities meant to cause fatigue all the time. We are primed to think that if we aren’t walking away crushed, it must not have been a good workout.

The secret to obtaining above average conditioning levels is adhering to a plan that allows for high levels of training combined with enough planned recovery time. This is not a new concept, recovery has become a buzzword within training for all the right reasons.

How we go about recovery is important. The “deload” term that gets thrown around generally involves deleting 50% of the training volume and intensity to “promote recovery”. Not only does this risk an athlete losing out on valuable training time, it can present an injury risk to the athlete when the intensity ramps back up.

There are three things to consider when creating a conditioning program.

Athlete individuality

Adaptable scheduling

Exercise selection

These are in no particular order, as importance falls on each. Finding athlete individuality within a training program includes the measuring tools that we use. Whether it’s a wearable, a post-exercise assessment or a combination, there needs to be an aspect of understanding the athlete’s individual response to exercise. Thankfully, we have easier access to wearables which give us the valuable information that we need. One person’s 150 bpm is another’s 170 bpm. Respecting individuality is critical to long-term success both from a progression perspective and injury-prevention.

Adaptable scheduling creates an opportunity for an athlete to adjust their training around lifestyle events that we all know happen. In baseball, rain-outs cause disruption to training calendars more than anything. In the gym, missed training sessions can completely dismantle a coach’s beautiful program if that program can’t adjust.

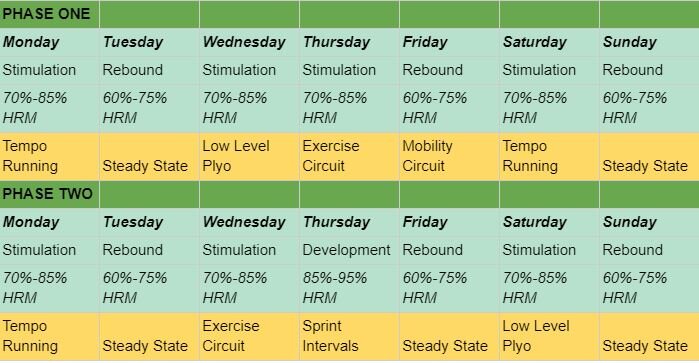

The best ways to make training adaptable is to work off of specific methodology. Jameson spoke about this in his Masterclass and I like his terminology. He uses the following training blocks (speaking broadly here).

Stimulation

Stimulation days involve training at mid-range heart rate zones (70%-85% Heart Rate Max) with classic volume and intensity progressions. This is where we find the majority of our training days in the early phases of a training program, as it’s vital that training volume is increased before training intensity. Utilizing low level plyometrics and tempo runs are two ways that I’ve incorporated stimulation days.

Development

Usually seen in later phases of conditioning programs, the development days are the times for an athlete to dig deep and find new levels of training. Utilizing higher intensities like sprint work, sleds or agility circuits are ways that I’ve incorporated higher intensities. It’s important to appreciate that these days are earned through adherence to stimulation days early in a training program. Development days also need to follow a structured schedule when addressing volume or intensity gains. It’s easy to get caught up in these days and go from development to overtraining.

Rebound

Rebound or recovery days are pivotal to an athlete’s success. I’ve seen many successful methods but none of them involve doing nothing. We can still train and introduce some training volume. It's important that we adhere to recovery periods and maintain heart rates in the training zones that we are looking for. For the sake of debate, I’ve had success with athletes working in the 60%-75% HRM zone.

Not only does introducing additional training volume help stimulate active recovery, it also gives us an opportunity to continue working on movement capacity or mental performance in a less intense environment, giving the athlete room to search and listen to their body and mind. Rebound days consist of mobility circuits, low level plyometrics or some steady state cardiovascular exercise.

Step Three - Every Exercise Is A Test

Testing and retesting is how we retain clients as fitness professionals. It’s how we show progress to other departments. Without a consistent structure for measuring results, how do we know what’s working?

The challenge that I’ve faced is assessments can be difficult. They can chew up valuable time and training stress, blowing up the flow of even the best programs. By building assessments into the program’s training days, we can better serve the athlete while accumulating much more data.

Take the Cooper run test. 12 minutes of running. For some, this is a challenge on its own. Taking that initial assessment and understanding what occurred can help us measure progress without having to do the test over again. There are other ways to progress than simply running father in 12 minutes.

What was the athlete’s heart rate while running?

What was the athlete’s 60 second heart rate recovery after the run?

What was the athlete’s RPE? (Rate of Perceived Exertion)

How fast was the athlete running?

Knowing these numbers and using them to test running days later in the training program can help us determine progress without retesting specifically. This could look like the athlete running at the same pace with a lower heart rate, improving their heart rate recovery following a development day, reporting a 6/10 exertion level for the same exercise that was an 8/10 earlier or simply performing better while maintaining the same heart rate markers.

Sample Training Week

Keep in mind this table represents training intensities only. Volume needs to be incrementally increased day over day, week over week to produce lasting change in targeted energy systems.

A final note is that if we are progressing athletes both with volume and intensity there needs to be a new baseline to be measured against. This is where a retest day might hold value but only if it is in the best interest of the athlete’s training and competition schedule.

Thanks for reading!